It was only two years after Stephen King’s novel Cujo was unleashed on the world, that the author’s rabid St. Bernard leapt onto theater screens in 1983 courtesy director Lewis Teague. King himself has ranked the movie among the greatest adaptations of his work, saying that if Kathy Bates most deservedly won an Oscar for her performance as Annie Wilkes in Misery, so too should Dee Wallace have taken home the honor for her portrayal of Donna Trenton. It is a tour-de-force performance, one that invokes at various times judgment, sympathy, and ultimately terror in its audience. Wallace, along with the young Danny Pintauro, are unforgettable in Cujo, leaving a lasting impression that would make just as many movie goers as wary of St. Bernards as Hitchcock made wary of showers.

In Lee Gambin’s new book, Nope, Nothing Wrong Here: The Making of Cujo, one might be surprised to find it’s not just Wallace and Pintauro that make the film work. Gambin’s painstaking research and in-depth interviews with nearly every person involved in the movie’s production shines a light on how the movie pays homage to everything from horror classics like Psycho and The Exorcist, to films about World War II. There is no stone left unturned in Gambin’s book, which somehow manages to read like a love letter to the movie without ever once becoming saccharine, indulgent, or biased.

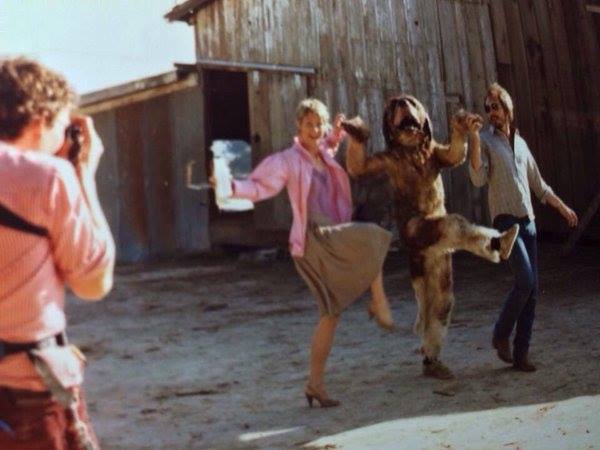

In short, Nope, Nothing Wrong Here is every Cujo lover’s dream come true. Any fan of the movie will be foaming at the mouth for its 200+ behind the scenes photos, most of which have never been seen, along with cast and crew members looking back on every minute detail of the film’s making.

Sechrest Things is proud to feature this exclusive excerpt from Nope, Nothing Wrong Here: The Making of Cujo by Lee Gambin, available now to order.

TOO MUCH OF THE TUBE, GUYS

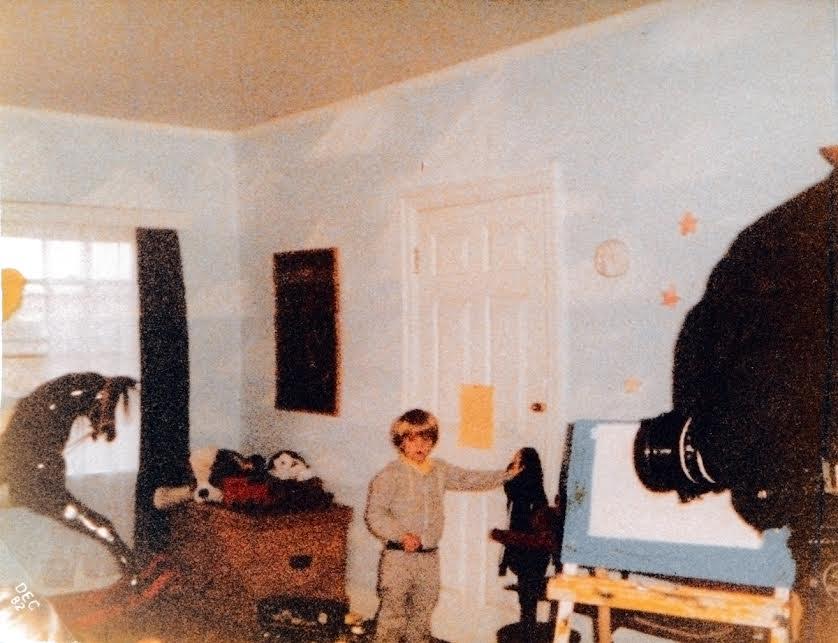

Tad sees monsters in his closet, so it’s mom and dad to the rescue.

Opening with Stephen King’s credit firmly secured over an image of a suburban house at night enveloped by oppressive darkness, this provocative visual is a sublime condensation of who the prolific and incredibly talented writer was at the point his novel Cujo was turned into a film: A master storyteller who got inside the homes of his readers to scare the living daylights out of them. By 1983, Stephen King would have written over ten best sellers starting with Carrie and had a number of filmic and TV adaptations come from them including Salem’s Lot (1979), The Shining (1980) and two released the same year as Cujo, being Christine, directed by John Carpenter and The Dead Zone, directed by David Cronenberg. Carpenter and Cronenberg were already at that point in their careers staple directors in the horror genre, and their cinematic interpretations of King’s work were box office draw cards and very well-received by critics.

Impressed with director Lewis Teague’s socially aware eco-horror hit Alligator (1980), Stephen King would suggest the Roger Corman affiliate to take the reins of his story about a rabid St. Bernard who traps a mother and her son inside a busted-up Pinto and take on the job of writing the screenplay himself. However, the studio green lighting the project being Warner Bros. signed on Hungarian director Peter Medak, who had left an impression with his incredibly impressive ghost chiller The Changeling (1980) and eventually King’s script would be rejected in favour of Barbara Turner’s who would end up being trimmed and reworked by follow up screenwriter Don Carlos Dunaway. More changes would eschew when Peter Medak would be fired from the project, ushering in King’s first choice for the film Lewis Teague as director. With this, Medak’s long-time friend and collaborator Barbara Turner would remove her credit from the film and use the pseudonym Lauren Currier.

Lewis Teague’s credit will scroll from behind the house in the opening titles, suggesting a playful graphic gesture departing from the standard fade in and out from the rest of the credit reel as the camera closes in on a set of two windows on the top floor of this large, white weatherboard two story. This is the home of the Trentons – a middle class family of three who will fall into a horror of circumstance. Zooming in on the Trenton house is atypical of masterfully concocted horror cinema, in that a lot of personal and character-driven horror movies hone in on the place of terror from the get-go, and also isolate the people or locales in question, closing in on the place of horror or the person it will most affect; much like the zoom in on Chris MacNeil’s (Ellen Burstyn) Georgetown house in The Exorcist (1973) or the dingy apartment used for lunchbreak rendezvous for Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) and her lover in Psycho (1960).

Here, we are introduced to the first human character of the film; six year old, golden haired Tad Trenton (Danny Pintauro). Tiny in stature, already incredibly vulnerable and with delicate cherubic features, the little boy is weary eyed in the bathroom, wiping his face as he finishes up at the toilet. The room glows with a warmth from interior lighting, framing Tad with a bronze hue – a color scheme that will become commonplace throughout the film. When he switches the light off, the scene is dominated with blues and blacks which makes a striking contrast against the orange tint. The art direction suggests this lovely Maine abode is a brand new home, with characters yet to settle in, and Tad’s bedroom is decorated with stuffed parrots and teddy bears, giving a sense of passivity and childlike frailty. Although there is a funny aside of a stuffed St. Bernard thrown in the mix, Tad’s bedroom is a pastel place of innocence with its walls painted up with a blue summer sky theme, floor boards polished and new and a large rocking horse set next to a closet packed with clothing and toys.

Within his comfortable surroundings however, Tad has distrust for something hidden away in his closet, and when he sees the door creak open, his eyes flare up with fear. There is an undisputed paranoia here, a little boy terrified of the lurking monsters that hide in the closet. This is an age old childhood fear, and something that director Lewis Teague taps into from personal memory – as a child he would imagine a wolf in his closet and under his bed and would have to race to the safety of his quilt and covers when the lights went out. In this sequence, the entire set up is just that: a child lost in the throes of an active imagination that jeopardises his safety.

The Barbara Turner screenplay with dramaturgical input from initially assigned director Peter Medak, uses Tad’s closet as a place where the ghost of a deceased serial killer (possibly Frank Dodd from The Dead Zone) haunts, but in the final draft of the script and eventual outcome of the film, the monster lurking in the closet would be a manifestation of the fears and anxieties Tad concocts from his overt sensitivity and awareness of his parents’ crumbling marriage. In Poltergeist (1982) released a year earlier, a child’s closet will also be the place of horror where little Carol Anne (Heather O’Rourke) is kidnapped by vengeful “TV People” and in horror outings such as Cameron’s Closet (1988) this horror embedded within a child’s wardrobe is exploited even further. Childhood delusions and the making of monsters is all part of the unique terror of the unknown, and monsters birthed from hypersensitivity and burrowed sadness is as extension of internalising social anxieties – something that Tad is most definitely susceptible to. Fear inside the comfort of the middle class household is a palpable pain for little Tad as he tries to navigate his control of his overwhelming and very personal terror.

If the Trentons have just moved in to this large Maine house, they are determined to begin a new life away from the big city, and the small town of Castle Rock (a fictional coastal town that is the locale for many Stephen King stories) seems to be an ideal place to raise a child; a healthier alternative to the “big smoke”. However, protecting their son from invading entities that haunt his closet is something that a sea change cannot fix – this is subjective and all about Tad’s personal demons and personal battles.

Monsters in Stephen King’s universe include the telekinetic Carrie who is pushed too far by her peers and oppressive mother, vampires who infest the entire town of Jerusalem’s Lot, zombie cats and newly resurrected dead children struck down by trucks, killer cars with obsessive desires and psychotic nurses such as Annie Wilkes from his book Misery who is the most earthy of the monsters on par with Cujo – however, the fears unlocked in a child’s mind play against those very tangible horror stories, and in this film, Tad’s dreaded anxiety comes to full realization when he is eventually faced with a blood stained, frothing two hundred pound rabid dog snarling at him.

The first word heard in the film is screamed out in absolute terror – Tad hollers “Mommy!” beckoning for his mother to come to his aid. A thematic condensation and precursor as to what is to come, Tad calling out for the comfort of his mother and ultimately being rescued by her will be the fundamental surface core to the motion picture. The final act of the feature will be summarised by the simplistic notion that a mother must do everything she can to protect and save the life of her child, and the film sets this up straight away with this scene. When Donna Trenton (Dee Wallace) enters Tad’s bedroom, she is followed by her husband Vic (Daniel Hugh-Kelly) and the duo come to the “rescue”.

Previously unreleased photo of Danny Pintauro (left), Dee Wallace (center), and Daniel Hugh Kelly (right).

Donna is a beautiful young woman with stylish short blonde hair and a slender dancer’s body and Vic matches her beauty with a lean athletic musculature and handsome features. Where Vic comes to represent the quintessential eighties urban professional (he is in advertising and a campaign runner for television commercials), Donna is a woman trapped by stifling repression – cornered into being somebody’s wife and somebody’s mother. As she shuffles over to her son and lovingly takes him into her arms, she asks “Bad dreams?” then scolds the role of television in her household with “Too much of the tube, guys”. The idea of television as a source of nightmares is something that horror films and other genres examine with upmost honest sensibilities, and in films such as Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist (1982) this is exploited in extreme measures where the invention itself swallows up little Carol-Ann. However, in Cujo, Donna’s comment is double loaded – here she is attacking the role of television as not only a nightmare inducer for her sensitive little boy, but also as the cause of distraction for her husband who works in churning out commercials that are wedged in between narrative based programming. As the film progresses and we learn of Donna’s infidelity, Vic’s career is scrutinized as something that is a constant disruption from his wife’s affections and his connection to her psychologically, emotionally and most explicitly sexually.

Vic goes through the contents of the closet and retrieves an “over the hill” teddy bear which is a comforting crutch that seems to be discarded by Tad. Or at least forgotten. Complacency and taking safety for granted is a theme that runs through the construct of Cujo, and even here in this tiny splice of “slice of life” melodrama it is made profound. Tad describes the monster in the closet to Donna and Vic (the monster’s eyes, its sounds etc) and in doing this, the image of the fearful wide-eyed boy sitting in the arms of his loving parents represents the child bringing his parents together through his paranoia and fear. When he is assured that “there are no such thing as real monsters”, Tad is put back into bed. This is the first time the film introduces this solid principle at its foundation and its base centre – the concept of monsters existing in reality. It also revels in examining what makes a monster a monster, the evolution of monsters, the face of the monster and what one must undertake in order to confront and vanquish monsters. Donna comforts Tad with “Over, done with, gone” – another repeated mantra that bonds parent and child and is used to treat dark situations ushering in fast and much needed light. In Cujo, there is most certainly the impenetrable world of darkness and monsters exist in the dark, however, what will eventually result and become a crashing reality for young Tad is that monsters will most definitely appear in broad daylight and lit by the flaring summer sun.

One of the most vividly inventive moments during this sequence draws its inspiration from the Russian film The Cranes Are Flying (1957). Directed by Mikheil Kalatozishvili, this film about the effects of World War II features a scene where a young boy is being chased by a German tank. During this moment, the camera turns upside down to evoke the feeling of this boy’s world being turned upside down. Lewis Teague and his cinematographer Jan de Bont, very much influenced by Kalatozishvili’s choice of camera angle to comment on character displacement, turmoil and upheaval, use this incredibly innovative technique when young Tad races towards his bed to escape the deadly grip of his closet monster, and dives into bed. When he throws himself into bed, the camera has completely flipped and it is as if little Tad has fallen into space – a refuge from the monsters that lurk on the ground. This moment adds a certain dreamlike quality to an otherwise very realist film; it is also one of three moments in the picture to use slow motion (the next time this occurs it will be inserted to emphasize pure unadulterated cathartic primal screaming and finally to transition from relief to the resurrection of the eternal monster). Besides lending itself to dream logic and artistic expression that comments on character (namely Tad’s extreme attempts to avoid hungry beasts lurking in the darkness), the flipping of the camera is a masterfully executed technical achievement and turns Tad’s falling into space into something that cements the film as one devoted to a stylish and unique vision. Cujo is most definitely a stylized film, and although it lives and breathes in melodramatic realism, it is ultimately a fairy tale and allegorical tale of fear (personal, imagined, real, tangible, familial, marital, economical, social et al) and therefore utilizes an aesthetic that passes comment on this.

The scene ends with Donna and Vic retreating back to bed. The lingering image of Vic standing at the doorway with the moonlight spilling onto him leaves a comforting reassurance that there are in fact “no such thing as monsters”. Here Vic stands shirtless and open, vulnerable and readily available to his wife and son; however, his wife Donna is dressed in a full bodied nightgown – her manner is sombre and downbeat, she is also “covering up” and concealing hidden truths. Costume designer Jack Buehler and his wardrobe assistant Nancy G. Fox would consciously bring this to the project, feeding character and subliminally suggesting acute insight into the very personal.

When Vic reassures Tad about the non-existence of monsters, Tad fearfully whispers

“Except for the one in my closet…” and the scene closes with an extreme close-up of Tad’s face, peering from under his covers, begging “Please…please…” He is desperate not to be traumatised by the monster lurking in his closet, and from a child’s psychological point of view, what he fundamentally wishes for is safety, sanctity, wholeness, togetherness and to not harbour feelings of unease about his surroundings. His “monster” is the fear imagined and concocted by a child fretful of his parents who may in fact not be in love. There is a fade to black here (the only one in the film) and when the time lapse to morning ushers in the following jump cut to the interior of Tad’s bedroom, we follow Jan de Bont’s camera to discover a closet door barricade. In a slight moment of comic relief (something that is decidedly very much unused in Cujo) the visual of everything in Tad’s bedroom used to keep the closet door shut closes the sequence and acts as a narrative launch pad for the following scene.

LEWIS TEAGUE (director): Tad’s fear of monsters in his closet and running to bed was all based on my recollections of me as a child when I had to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night. I used to have to turn out the light and in my mind I had to race to the safety of my bed before I hit the light switch, or else the wolves would come out from underneath my bed and kill me. It was a game I played with myself. I knew it wasn’t true, but it was fun to do that as a kid – to make sure I could hit the bed before the lights went entirely out. I told Danny about that and he understood all that right away. He was a smart kid. I then discussed it with Jan de Bont and how to make it scary and the drama came from the time period from where he is a blacked out room to him reaching the bed. So I thought we should stretch out the room when he hits the light switch. So we built a set for the extended room. Before he hits the light switch we were shooting from a real life location bedroom, and once the lights are out we built the room. The distance between the light switch and the bed was more than five metres away and to make it more fun I suggested to Jan that we do a flying shot and Jan was very well versed in films and understood what I was asking for. We wanted the camera to go upside down so that when we shot it in slow motion and he jumps into bed, it looks as though he is falling into an abyss. So Jan built a little contraption in the room that he could get up on and get that shot. The production designer was Guy Comtois who had already designed Tad’s bedroom before I arrived on set. This was all designed while Peter Medak was on the film. I thought it was great and I loved Guy’s work so much I hired him again on Navy Seals (1990). As much as he had designed everything before I had got there, Guy would discuss everything with me, and he was one of the hardest working people I had ever met. It was a wonderful relationship. He had great taste and an amazing eye for detail.

From Danny Pintauro’s private collection of photos,

exclusively available in ‘Nope, Nothing Wrong Here: The Making of Cujo’ by Lee Gambin.

MARGARET PINTAURO (Danny Pintauro’s mother): The whole monsters in the closet scenario in the film was pretty funny, because Danny never experienced monsters under his bed or in his closet when he was a little boy. That was all acting!

DEE WALLACE (“Donna Trenton”): In the interim between The Howling (1981) and Cujo, I had done E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) which was a huge blockbuster and the producer of Cujo, who also worked on The Howling, Dan Blatt asked me to come in and star in it. He also said that he wanted my husband Christopher Stone to play my lover. Dan knew how tight we were, so he offered us both the film. So I thought about it and asked to see the script and it was a huge tour de force for a woman, so how could I say no to a script like that! So we were off and running.

DANNY PINTAURO (“Tad Trenton”): I don’t remember anything about the audition. The only thing I remember, and again, this is hearsay, this comes from my mom telling me the story, and I do remember doing this; after every audition that I did, she and I had created this idea that, you know, bless my mom and her heart; she really is the one who made things so much easier for me overall as a child actor. I would leave every audition, whatever it was for, whether it was for something important, or a commercial or print ad, and she would say “Alright, what do we say?” and I’d say “If I get it, I get it. If I don’t, I don’t.” And what she said was that we were going up the stairs, in a hallway like in a stairwell and one of the producers, I think Dan Blatt was walking down the stairs and he heard me say that and that was what persuaded him to give me the job, that I was very simple and to the point of saying “Yeah, I get it! If it works, it works. If it doesn’t, it doesn’t! I’m good with that.” That’s all I know. Yeah, that’s all I know. Again, that’s my mom! I’m curious to actually hear what they say!

DANIEL HUGH KELLY (“Vic Trenton”): I was in Chicago and I just finished up on a series for NBC and returned to New York, so I had gone back home and I was doing a play and my agent called, and I am sure that was David Guc. He talked about it and I don’t recall if I had to audition. I may have had to, but I don’t recall. But I do however remember most significantly going out and getting a copy of the book Cujo, and I read the book and I had never read any Stephen King stuff before, because I’m not a big fan of horror, but I genuinely enjoyed the book a lot. After I got hired I re-read it and that was just me doing my homework and working on the backstory for this character, getting to know him and what he was about. But that can be a double edge sword because you see what Stephen King was doing and I thought that that was very good – some people may dismiss his writing these days – but certainly at the time, I thought that that book was very good and very well written, but when they started changing things once the screenplay was written it was incredibly upsetting to me. But that is naiveté on my part because books are always changed, I mean they even changed Tennessee Williams’ work when they did films such as A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). So I remember that and I remember casting director Judith Holstra was around, and I had to meet with her. Marcia Ross may have been in the room as well, but Judith was definitely involved and I really loved her. I also met with the original director on the film Peter Medak and I really liked him, and I remember I was sent a script while I was doing the play and I couldn’t get to the script as soon as I wanted. So, I read it just before we started shooting and I remember thinking “Hang on a minute! This is not the book!” It was very upsetting to read this script and see how different it was from the novel. I thought, “Wait a minute, you could have so much more in it than what you have here”. Then when we got on set it was changed several times more.

LEWIS TEAGUE: Well, there were two things I wanted to do: one was have a few very scary set pieces in it, and I spent a long time setting out to achieve that. And the other thing I wanted to do was make it as expressive and stylistic as possible. So I would ride out to that set when I wasn’t riding with the makeup girl which only happened once. I would usually ride with the cinematographer, Jan de Bont, and talk about upcoming scenes, but try to talk about them at least in two weeks advance, to give him opportunities to prepare for them. I wanted to do half cinematic flourishes and scenes. For example, in the opening when Tad turns off the lights in the very beginning of the film and he is coming back from the bathroom and he turns off the light in his bedroom and has to get from the light switch into bed before all the light disappears, well that was all based on my childhood fears. I would have to flick off the lights and get into bed as quickly as possible – so I discussed with Jan how to do it. I said “Okay, we’ll have a couple of different bedrooms, so that when the light goes off the bedroom can expand in size, so the distance to the bed will be magnified”. And then also, Jan was well-grounded also in film history too, so, I said it would be a lot of fun to do the amazing shot from the film The Cranes Are Flying (1957) and he knew what I was referring to. The Cranes Are Flying is a Russian film from the fifties which has a shot at the end of the movie where the camera goes upside down when a kid is running off across a field, trying to escape a German tank and so that gave Jan the idea to build a set and build a superstructure to hang the camera from so it could go upside down. It went into slow motion when the kid is running across the room. The kid runs underneath the camera and the camera follows him upside down as he is jumping onto the bed, it almost looks like he is falling into space. I was looking for those kinds of shots and things. There is another shot in the film later inside the car where I wanted a three hundred and sixty degree spin. Dee Wallace has been bitten by the dog and she manages to fend him off and get back into the car and slam the door shut and she feels like she is passing out from shock and the pain of being bitten, and Tad is in the back screaming. The camera pans to her and never stops moving, and then pans off her and moves around to Tad screaming and then completes a three sixty back to Dee telling him not to open the door no matter what, and then back to the kid screaming. And the continuous motion it speeds up to a blur. I would pose these problems and challenges to Jan and then he would figure out a way to do it. In that particular case, he gave it some thought, he went out and bought another car and he built a superstructure on top of the car, so the camera could be above the car shooting down into it with a periscopic lens and the whole thing mounted on a gimbal that could spin around. So he was very cleaver. Jan wasn’t afraid of work. One thing Jan was not afraid of was work! If he had a challenge, he’d get his teeth into it, he’d figure out a way to achieve it!

CHRISTOPHER MEDAK (production assistant): Working on something like Cujo compared to something like Chained Heat (1983) is complete night and day. The first film I ever worked on was The Jazz Singer (1980), I was a copy boy and tea boy and operator of the Xerox machine in a little office, that was my first job in the industry – and then coming in to do something like Chained Heat was once again completely different. It was a such a bad B movie, it was shocking. It was absolutely insane, I remember the make-up artist knocking out the director. There was a wrestling scene and they were going at it and she climbed into the ring and knocked the director out. She was a feather of a girl too! But I guess the similarities between Chained Heat and Cujo was the fact that neither films had a crew that had a love for their producer.

DEE WALLACE: I remember Lewis explaining the camera angle for the scene where Danny runs to his bed. Lewis was incredible. Also, the monster in the closet is real for every child, and Lewis wanted to do it in a very realistic point of view. That great shot of Danny running a very, very, long way to his bed gives you the feeling of the panic mounting up in this little boy and that begins taking the audience on its own ride because we all remember those times when we were little and so frightened about the Boogey Man in the closet or the monsters at Disneyland. I mean look at all the Disney films, they have such strong monsters and villains.

CHARLES BERNSTEIN (composer): It’s a great, great gift when a filmmaker gives a composer the opportunity to just work with image and music; it is a gift that we don’t always have. We’re often under dialogue, we’re often buried under sound-effects, and so the scenes in this film are like gold to a composer, because our opportunity to be a major part to the storytelling is essential. I think most composers have a favourite scene or scenes they have done over time. I love the whole opening of Cujo. There is just a glorious moment when the little boy comes back from the bathroom and he turns the light off and he runs to his bed because he doesn’t want to be vulnerable to any monsters from his closet. So he first tries to turn the light out and he fails and it always gets a little chuckle from the audience. Then he goes back and he really concentrates, and the music that carries him from the light going off until he gets in his bed, under the covers, is expressed by a brilliant shot by Jan de Bont, crafted by Lewis Teague, where the camera flips upside down and captures his run – and then when he jumps into bed the camera kind of catches him from another angle. It’s a beautiful camera move and it gives the music the opportunity to really do something special. So I was able to play the theme with a descending shallow line, kind of a chromatic descending shallow line, and to me, it was just a cinematic magic moment, from the time the boy turns the light off until he kind of snuggles down into his bed. That was one of those moments where the music can do what it needs to do and not be interfered with. I treasure that!

PETER MEDAK (originally assigned director): When I came onto the project, the original script by Stephen King was not very good. The producer Dan Blatt came to me and had this lady he was good friends with who was an excellent screenwriter, and this was the very talented Barbara Turner, who eventually refused to use her name on the project after I was fired, because she and I were incredibly close. I mean we were very, very close – we were best friends. So she was pissed off that I was fired and used an alias for the movie, which was Lauren Currier. She was so angry about that because she was so proud of her work on the film, and her writing was just perfect. The script she wrote for Cujo was excellent. Barbara was just beautiful. After we worked together on Cujo, she wanted me to work with her on a Jackson Pollock movie, and it was a major tragedy when she passed away. She remained a great friend until the end.

LEWIS TEAGUE: I wasn’t trying to eliminate any of the supernatural elements when I first started thinking about it. That came later. For example, I really wanted to suggest something supernatural in Tad’s closet that scared him at night; even though that he couldn’t convince his parents that there was something lurking in there. The thing that attracted me to the story was the fact that all the characters were real and well developed, and I saw that they were all reacting to fear. That had sort of been an interesting topic of exploration in my own life to try and distinguish between real threat and the imagined threat – to not be afraid of things that aren’t real. For example, if I step out into the street and glance up just in time to see a Greyhound bus tearing down on me, that’s something that deserves my fear and the fear will galvanize me to jump out of its path quickly. But, if I’m worried about how a film is going to turn out or worried about how I am going to pay the rent at the end of the month, or worried about a particular relationship – well those are all imaginary fears because they are not happening in the present. They are things that I am worried about that might happen! The problem with that is the brain; if I start worrying about paying the rent and get scared from that, then the brain thinks that it is a real threat and starts putting me through the biochemical changes that one goes through when there is a real threat. This goes back to caveman times when a sabre-toothed tiger would jump out from the bushes and the caveman would have a few seconds to prepare to fight or run. So the body goes through all these biochemical changes that would enable the caveman to fight or flight… fight or flee. And the problem is that back in those days the threat was over in a couple of minutes – the caveman either got eaten or got away. In any case, the threat was over and his body chemistry could then return to normal: the heart rate would slow down and the gastrointestinal track would start doing its job. He would stop flooding his body with adrenalin and cortisol and all that kind of stuff. But in today’s society or in the society of Cujo and in the environment where the characters are living the threat was continuous. The father is afraid that he is not going to be able to feed his family when he loses the contract. The mother is afraid that she is going to grow old and waste away her life in this small town in Maine. And what the problem is when people believe that their fears are real – like she believes that she might waste away her life and then they start acting on the fear they start making stupid choices –for example she decides to have an affair with a local tennis bum. Choices made on the basis of fear are inevitably going to get into deeper trouble and that is what happens in that story. That is what I read and saw happening in that story. That was an important theme in my own life – it is a very important phenomenon that I have learned to deal with. So that I do not waste my time and energy worrying about things that aren’t real and that is what I read in the book and that is what attracted me to the story.

MARCIA ROSS (casting director): I was working with a woman named Judith Holstra, who I worked with for eight years, and we had a company called Holstra-Ross Casting. Judith had a long relationship with Robert Singer and Dan Blatt, and Dan in particular she had worked with on a number of times, and that’s how we were offered to work on this film. I think Dee was attached from the very beginning, she had come into the project quite early. She had become quite the star, just coming off E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial and was a kind of motherly role and plus she had a name that we needed to go with the film. And then after we had Dee instantly involved, we started the casting process. The thing that I really remember the most was the fact that I went to New York. I went to New York City and Martin Gage who was a top agent, who is still alive and he’s a wonderful man, let me use an office, like a room in his office, which was great. So I did auditions in a room at his office and one of the people I found from New York was Danny Pintauro. Daniel Hugh Kelly, Judith and I knew. We cast him in 1981 from a soap called Ryan’s Hope (1975-1989), and Judith and I were big fans of his, so we had cast him in a pilot called Murder Inc. in the winter of 1981. So we knew him, Judith and I were big fans of his, and so we cast him in this pilot with Tovah Feldshuh for CBS. John Avildsen directed, so we knew Daniel.

LEWIS TEAGUE: All of the house’s rooms were all actual locations. The only set we had was the elongated bedroom and that was shot in a warehouse somewhere in Mendocino.

ROBIN LUCE (make-up): I had not read the book, but I knew of Stephen King of course and was very excited to be invited to work on a Stephen King project. Once I read the script I thought it was going to be an excellent challenge for me, especially being the start of my career, this whole concept of being able to portray what these two characters will be going through stuck in this car. I think I got the Stephen King draft of the script because I was brought in very early in the game.

ROBIN LUCE (make-up): I had not read the book, but I knew of Stephen King of course and was very excited to be invited to work on a Stephen King project. Once I read the script I thought it was going to be an excellent challenge for me, especially being the start of my career, this whole concept of being able to portray what these two characters will be going through stuck in this car. I think I got the Stephen King draft of the script because I was brought in very early in the game.

DANIEL HUGH KELLY: I don’t remember the connection Cujo was meant to have to The Dead Zone but maybe that was in the original draft that Stephen King had written which I never read. I still have a copy of my novel of Cujo and I have all the important sentences underlined in yellow. The script that Barbara Turner wrote was great, but the draft that Don Carlos Dunaway did – well, I didn’t care for that. But I agreed to do the movie, so suddenly I was locked down.

MINA BADIE (daughter of screenwriter Barbara Turner): My mother and Dan Blatt had a rough time during that project, but remained friends until Dan’s death. I believe Dan Blatt told my mother that she ‘would never work in this town again’ after my mother took her name off the film and used her pseudonym – created, I believe for that movie.

PETER MEDAK: Barbara and I decided to re-add the supernatural element into the story. Barbara’s original screenplay opened with the little boy going to sleep in his bedroom and the closet door was opening and something was coming out – a ghost, or a spirit or something. The child screams and wakes up and we realize he is having a nightmare and the parents run in and so forth. Because of my kind of mania, when I did The Changeling with George C. Scott which was a great experience for me, I always wanted to do more movies concerning the supernatural and whatever picture I got I used to twist some kind of supernatural element into it; obviously not everything, but the films I could. Barbara and I had figured out that in the little boy’s closet was he ghost of somebody who hung himself. This was an old house, and the ghost of a man who killed himself would haunt this little boy. He was a murderer. A killer with no remorse. Also, his ghost would later on infect the bat that would later on bite Cujo so there was a plot that was following it through. But had I made the movie, I would have made Cujo into a supernatural horror story. It would have been influenced heavily by Hitchcock. But of course I was fired.

LEWIS TEAGUE: I had seen the other films based on Stephen King novels and was familiar with them, but they really didn’t enter into what I was doing at the time. I guess I really came out of a neo-realist school of filmmaking and Stanley Kubrick who did The Shining (1980) and Brian De Palma who did Carrie (1976) were far more expressionist in their approach. I’m more of the school of classicist realism which is why I didn’t mind losing the supernatural element. I did try to keep the idea that there was something demonic in the closet that was scaring Tad; and I actually even shot something with that in mind adding special effects later. But it wasn’t really working and it seemed a little hokey. It just seemed better to drop that and let it be in Tad’s mind. What it was originally was a form of some monster in the foreground I concocted and lit with sheets of rubber, so when you are looking at it from the monster’s perspective from inside the closet it looked frightening but looking at it from Tad’s perspective it looked was hokey. We started shooting and I thought this is not going to work, so let’s take it out!

PETER MEDAK: I never met Stephen King. I doubt if Lewis ever met him either. By then, Stephen had become a massive writer. I remember The Dead Zone being a backstory for Cujo, but that was never part of Barbara’s script. Because of that, she and I developed an original idea which would involve a serial killer who kills himself in the boy’s closet – he hangs himself, and his ghost returns there to haunt this little boy.

MARGARET PINTAURO: The producer Dan Blatt came to New York and asked for Danny to come and audition and he hired him immediately. So we flew out to California and that’s how simple it was, that’s how it all came about. I didn’t know anything about the project. I don’t remember any other boys auditioning for the role. Dan strictly came for Danny and Danny had the part straight away. For his audition he had to read from the script, but I don’t remember what scene it was. Dan knew he wanted Danny from the start, because Danny was on As The World Turns (1956-2010), and Dan had seen him on that. Of course after doing Cujo, Danny had gotten the role on Who’s The Boss? (1984-1992). That was all because of his work on Cujo. A woman executive from Who’s The Boss? saw Cujo and she flew Danny and I out for an audition and he got that show straight away. Danny never went back to As The World Turns after Cujo. There was no screen test for Cujo, Dan Blatt came for Danny with Danny in mind.

PETER MEDAK: When I was a young assistant director I worked on some Hammer horror movies, which I loved. I was very fortunate. When I came to America I was just as lucky to work on Alfred Hitchcock Presents. I always had this keen interest in quasi-horror subject matter, so I really wanted to make a lot more of these films. The film I did before getting Cujo was The Changeling, and that was a supernatural ghost story. I was attracted to Cujo, but the film I would have made would have not been Lewis’s, I’d have made a very different movie. I definitely wanted to give Cujo that supernatural edge with the serial killer and his connection with the dog. Stephen King had that in his novel with the killer from The Dead Zone, but here I wanted the killer to be a suicide that happened in the attic above the little boy’s closet and he would go over and visit his own grave then return to the closet. Barbara fleshed it all out and she wrote that the boy’s closet door would keep opening and there was a beautiful connection she made between the ghost and the bat that eventually infects the dog. I like what Lewis did with the opening with the dog going over the brook and chasing the rabbit and getting his head stuck in the cave, I mean all of that was mine. Not that I claim any credit there after all these years, but aside the years, there is all the work you put into it – but I think Lewis did a fabulous job.

CHARLES BERNSTEIN: In a lot of ways film music, when you trace everything back, sort of starts around the year 1600 with the beginnings of what came to be called “the classical opera.” Opera did develop this concept over the years which was most fully realised with Wagner, of having themes he called “leitmotif” in German. This was the idea that themes were all stated throughout the process. But often in opera there is an overture and the themes are introduced. In musical theatre, in which Rodgers and Hammerstein were the highest manifestation of in America, is kind of modelled after opera and film kind of grew out of that era as well. So a lot of the earlier films, big movies, would have intermissions and a walk in and walk out tracks. This is all part of the filmic musical experience derived by musical theatre and its ancestor the opera. For Cujo, I did not assign character themes, but I did assign circumstantial character themes, and by that I mean there were overriding themes like Cujo has his own personal theme; and the little boy has his piece of the main theme which is more delicate and more pianistic, like when the camera comes in on him in the bathroom in that opening scene; you start to feel the treatment of the theme for the little boy. Also, when the little boy has his Monster Words and the dad reads it and so forth; it’s kind of a treatment of the theme for that tender boy moment, comforting the boy against the monster moment and so forth. So, in essence there are these overriding themes, but they are treated in certain ways for the mother and son and certain ways for the boy on his own, and for the father with the boy and certain ways for the unhappy martial issues and so forth.

DON CARLOS DUNAWAY (co-screenwriter): Barbara Turner did a super job on the Cujo siege, which tracks pretty much as she wrote it. She cut some of the advertising stuff, but not enough. There was quite a bit more Donna/Vic stuff, maybe more Donna/Kemp. There was also quite a bit of explicit ooga-booga – supernatural things going bump in the night, special effects, etc. I took out everything I could on the theory that if you have a perfectly set up rational explanation for the bad stuff (rabid bat bites otherwise nice dog) the supernatural stuff is redundant and distracting. Writers like you yourself Lee Gambin, have stated that the film of Cujo is unusual for Stephen King simply because it lacks the supernatural; frankly, I can’t remember if that was my impression of the novel or of the King script, but I’m pretty sure the Turner script had a lot of supernatural elements in there. I tried to squeeze all of it out of the script, but see in my copy of the shooting script there were traces of it in a couple of stage directions that Barbara wrote, so I must have missed them. I consider that my most important contribution to the film was eliminating the supernatural aspects. Lewis actually shot some kind of cheesy special effects in post for Tad’s closet, but I’m pleased to say I was able to talk him out of using them.

PETER MEDAK: You know I have quit more movies than I have made. I think I have quit twenty movies in my career. When a director walks away from a film without making it, every frame remains in your brain. And this was the same with Cujo, but I completely closed my eyes to it. It was the most dreadful experience of my life. Dan Blatt used to be a lawyer working for Edgar J. Sharrick, who was a New York producer, and Edgar came to me because he loved my movies The Ruling Class and The Changeling and various other projects, and he was always there in these meetings, and he would have this nervous habit of picking his nails. And I was going to make a movie for Edgar called I Never Promised You A Rose Garden with Charlotte Rampling and Mick Jagger and God knows who else, and the movie never happened, but that’s how Dan and I knew each other, through Edgar.

For hundreds more behind-the-scenes exclusive photos and interviews, order your copy of Nope, Nothing Wrong Here: The Making of Cujo by clicking here.

Also if you’re like me, this article probably made you want to watch Cujo. You can get Cujo on blu-ray, DVD, or watch it now in streaming HD on Amazon Video by clicking here.

Editor’s Note: This content is copyright Lee Gambin, and is not to be taken in any way, shape, or form without permission.

Congratulations Lee ! Thanks for your work… Nancy

It’s such a wonderful book! Hope every CUJO fan runs out and buys it!

Awesome excerpt, super educational. Will check out the book.

[…] In the 2017 making-of book Nope, Nothing Wrong Here (the cereal spokesman’s goofy catchphrase) Medak said Barbara Turner penned an “excellent” script because King’s original “was not very good.” […]